Citizenship Education for Refugees

The problem of citizenship education for migrants, especially for forced migrants (refugees), has long been of interest to scholars since countries that receive migrants are interested in the quick and smooth adaptation of new members of their civil communities. The problems appearing in this process make it necessary to develop scientific approaches to the adaptation of migrants and refugees in new countries for them.

The last major issue of citizenship education for migrants that the European Union faced concerned refugees from Syria, from which almost half of the population has left since 2012. According to the United Nations (UN) Commission for Refugees, the number of forcibly displaced people as a result of the civil war in Syria will reach 7 million people in 2022.

The general flow of refugees to the European Union showed that as a result of political crises in neighboring countries, a certain flow of refugees has always arisen, in particular, after 2020, from Belarus.

Today, during the war in Ukraine, the world community witnesses the largest refugee crisis in Europe since the Second World War. The number of people who left Ukraine in 2022 as a result of the war has already exceeded the number of those who left Syria in just one year. Already in September 2022, according to the UN, the number of Ukrainian refugees registered in Europe exceeded 7 million people.

According to the human rights commissioner of the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine, as of December 1, 2022, “there are 4.7 million internally displaced persons registered in Ukraine. More than 14.5 million Ukrainians left after February 24, and at least 11.7 million entered the EU countries. 7.7 million are registered in Europe as recipients of temporary protection”.

European countries receiving refugees try to see them not as a problem but as resources for their future growth. According to scientists’ calculations, an increase in the share of migrants in the population structure of EU countries by 1% increases the GDP per capita of EU countries in the long term by 2%. The effect is obvious.

However, first, the countries of the European Union need to invest in social adaptation, retraining and citizenship education of refugees.

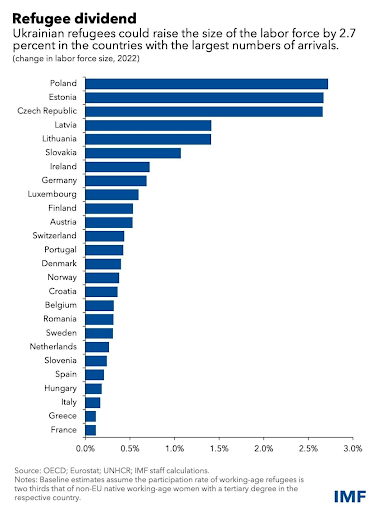

According to IMF data at the beginning of December of this year, the total EU spending on refugees from Ukraine amounted to about 37 billion euros, that is, 0.2% of GDP. In Poland, the Czech Republic and Estonia, this indicator is much higher – 1% (see the Refugee dividend figure).

At the same time, the labor resources of the EU at the expense of refugees from Ukraine increased by 0.6%. In some countries, it is much more – up to 2.7%, particularly in Poland, the Czech Republic and Estonia.

It is obvious that the EU is investing in developing its economy by helping refugees from Ukraine. It means that each additional Euro of such investments will decrease the number of Ukrainian citizens who will eventually return to Ukraine. This conclusion also applies to refugees from all other countries. The competition in the global labor market for educated refugees has long started and continues now. The IMF emphasizes that “although refugees initially form a financial burden, after 8-16 years, almost all become net taxpayers.” The benefits of refugee integration policies are considered to outweigh the short-term costs of early-stage assistance.

The interest of the refugees strengthens conclusions regarding the interest of the EU countries in integrating refugees. The results of a recent study by the European Agency for Refugees and the International Organization for Migration show that half of the 4.6 million Ukrainian refugees of working age chose the country for relocation, given the possibility of employment there. Thus, the European Union received labor migration caused by the war.

At the same time, the International Labor Organization recently reported that 28% of the 4.6 million Ukrainian refugees as of December 1 had already found a job, i.e., more than every second among those refugees who chose the country of relocation specifically for employment. It means that in 6 months all 2.3 million Ukrainian refugees motivated for employment will be employed.

According to research by scientists from the University of California, maintaining one Ukrainian refugee in European countries in 2022 will cost 8-10 thousand euros. Given the labor productivity in European countries, each refugee working in Europe contributes 40-50 thousand euros to the GDP of European countries. It means that the acceptable ratio of working to non-working refugees in Europe starts from 20% of working people.

By 2022, the indicator of 20% for Ukrainian refugees has already been exceeded in most European countries, except for Switzerland, where it is less than 10%, and Belgium, approximately 15%. In most other European countries, the figure is higher than 20%, but it is worth noting that this is the share of employed people only among those of working age who received temporary shelter. At the same time, there are currently many Ukrainian women with children in the EU who cannot always work full-time.

In any case, the socialization of refugees is an important goal of the EU from an economic point of view. The refugee integration programs usually include language and citizenship education courses.

At the same time, unlike the Syrian refugees, a large part of the Ukrainian refugees was aimed at a quick return to Ukraine, as soon as the war ends, or at least the stay in Ukraine will not be too dangerous.

It leads to a significant difference in the motivation of Ukrainian refugees to attend long-term political education courses in EU countries, which distinguishes their educational needs from the needs of previous waves of refugees, who were more focused on staying in EU countries.

Therefore, we decided to conduct a survey of refugees from Ukraine regarding their current needs in citizenship education. We used a questionnaire to survey the needs of citizenship education before the war in Ukraine began.

We interpreted citizenship education in this approach as education to successfully and effectively live together (in a family, in a community, in a certain country, in the whole world, in harmony with nature).

In the scientific literature and in practice, there are different approaches to the definition of civic education and civic competencies. In the headline of the survey we warned the respondents that by civic education we mean the process of developing skills, knowledge and values that are conducive to active and responsible participation in public life.

The question was posed in such a way that the respondents could rate each thematic area in civic education on a scale from 0 to 10 (where 10 is an acute deficit and 0 is a lack of need). We identified 9 such areas: human rights and freedoms, personal growth, communication, family formation, formation and development of communities, cultural / national identity, interaction with authorities, understanding the global context and environmental education.

The basis of the survey questionnaire was the following question:

“In which areas of citizenship education do you lack knowledge and would you like to study?”:

- Human rights and freedoms (Formation of respect for the honor and dignity of a person, for his/her rights and freedoms; Universal Declaration of Human Rights; ability and skill to protect human rights and freedoms; legal literacy; legal awareness)

- Personal growth (Interaction with personal goals / resources: critical thinking, media literacy, digital literacy, creative thinking, self-learning / lifelong learning, strategic thinking, management of personal resources (time management, management of personal finances, etc.), motivation management, emotional intelligence, decision-making in conditions of uncertainty, generation of new ideas).

- Communicativeness (Interaction with other people: tolerance, mediation skills, reputation building and management of reputational risks, ability to establish and maintain personal contacts and social ties).

- Family formation (Interaction within the family: the ability to form and maintain strong social ties, responsible parenthood / motherhood, safe sex, genealogy, gender roles in the family, age psychology, family budget).

- Formation and development of communities (Interaction with the public: leadership, teamwork, self-governance and management of common resources, economic development of communities, social innovations, project management, attraction of finance, development of social capital, social entrepreneurship, understanding of local self-government mechanisms, active citizenship )

- Cultural/national identity (Interaction with the cultural community (people): understanding of national-cultural identity, ability to preserve folk traditions, understanding of the national memory importance and its influence on socio-political processes (knowledge of national history).

- Interaction with authorities (Interaction with authorities: understanding the state structure, building transparent interaction, advocacy/lobbying, non-violent resistance, regulation of changes, understanding democratic views and values).

- Understanding the global context (Interaction with the world: cultural education, understanding the sustainable development principles, building an information society, respect for other cultures and ethnic groups, knowledge of world history, understanding the context and mechanisms of international relations).

- Environmental education (Interaction with nature: environmental protection, nature use, waste sorting, humane treatment of animals).

Surveys that we conducted among Ukrainians a year before the war had the following results:

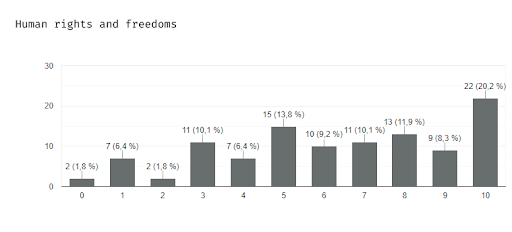

1) Human rights and freedoms. We understand this as the formation of respect for the honor and dignity of a person, for his rights and freedoms; knowledge of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights; ability to protect human rights and freedoms; legal literacy; legal awareness, including: acceptance of the principles of the rule of law, knowledge and awareness of one’s own rights, ability and readiness to defend them in life.

The respondent had to assess the level of need for this set of knowledge and skills on a scale from 0 to 10. If the respondent had an acute need to study this area – he chose the mark “10” on the scale, if he did not feel any need in this area at all – he chose the mark “0” on the scale. Interpreting the answers of the respondents, we can assume that if a person experienced a strong need, but not an acute one, he chose marks in the range “7-9”; if a person experienced a moderate (average) need, he chose marks in the range “4-6”; and if he felt a weak need, then he chose marks “1-3”.

According to the results of the survey, the respondents who defined their need in the field of “human rights and freedoms” as “acute” make up 20,2% of the respondents. The respondents experiencing a “strong” need made up 30,3% of the respondents. “Moderate” need was noted by 29,4%. A “weak” need was noted by 18,3% of the respondents. And the lack of need was indicated by 1.8%. As a result, 79,9% of respondents noted a moderate or high interest in the field of civic education “human rights and freedoms”.

2) Personal growth. By this we mean interaction with personal goals / resources, critical thinking, media literacy, digital literacy, creative thinking, self-study / lifelong learning, strategic thinking, personal resource management (time management, personal finance management, etc.), motivation management, emotional intelligence, decision making in conditions of uncertainty, generating new ideas.

The respondents who defined their need for the area “personal growth” as “acute” make up 22,9% of the respondents (the highest indicator among all areas). The respondents experiencing a strong need made up 43,1% of the respondents. A moderate need was noted by 22%. A weak need was noted by 9,2% of the respondents. The lack of need was noted by 2,8%. As a result, 88% of respondents noted that they have a moderate or high interest in such area of civic education as “personal growth”.

3) Communication. For this area we collected the knowledge and skills that are responsible for the interaction of a person with another person: tolerance, the ability to conduct dialogue and discussion (to hear, listen, persuade, argue one’s case), confidence in public speaking, conflict management, facilitation and mediation skills, building a reputation and managing reputational risks, the ability to establish and maintain personal contacts and social connections, empathy.

The respondents who defined their need in the field of “communication” as “acute” make up 16,5%. The respondents experiencing a strong need made up 33,9% of the respondents. A moderate need was noted by 34%. A weak need was noted by 12,9% of the respondents. The lack of need was noted by 2,8%. As a result, 84,4% of respondents noted that they have a moderate or high interest in such area of civic education as “communication”.

4) Family formation (interaction within the family). We understand this as such knowledge and skills as the ability to form and maintain strong social ties, responsible parenting / motherhood, safe sex, knowledge of genealogy (history of one’s family), understanding of gender roles in the family, knowledge of developmental psychology, the ability to manage the family budget.

The respondents who defined their need in the area of “forming a family” as “acute” make up 13,8%. The respondents experiencing a strong need made up 29,3% of the respondents. A moderate need was noted by 27,6%. A weak need was noted by 20,2% of the respondents. The lack of need was noted by 9,2% (the highest indicator among all directions). In total, 70,7% of respondents noted moderate or high interest in this area of civic education.

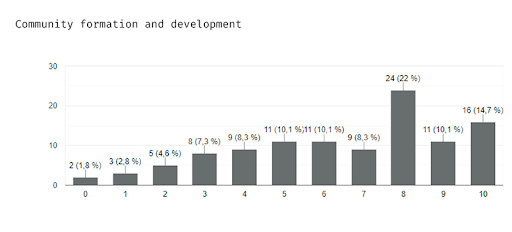

5) Community formation and development. This block includes the knowledge and skills that are responsible for human interaction in the community: leadership, teamwork, gender equality, minority rights, interaction during a pandemic, self-government and management of the shared resources, economic development of communities, social innovation, social mobilization, project management for the development of communities, fund-raising, development of social capital, social entrepreneurship, understanding the mechanisms of functioning of local self-government, active citizenship (activism).

The respondents who defined their need in the field of “formation and development of communities” as “acute” make up 14,7%. The respondents experiencing a strong need made up 40,4% of the respondents. A moderate need was noted by 28,5%. A weak need was noted by 20,2% of the respondents. The lack of need was noted by 1,8%. In total, 83,6% of respondents noted that they have moderate or high interest in this area of civic education.

6) Cultural/national identity. We understand it as the knowledge and skills that ensure interaction with the cultural community (nation/people): understanding of national and cultural identity, the ability to preserve folk traditions, understanding the meaning of national memory and its impact on socio-political processes (knowledge of national history), patriotism.

The respondents who defined their need in this area as “acute” make up 12,8% of the respondents (the lowest indicator among all areas). The respondents experiencing a “strong” need made up 33% of the respondents. “Moderate” need was noted by 32,1%. “Weak” need was noted by 17,4% of the respondents. The lack of need was noted by 4,6%. As a result, 77,9% of respondents noted that they have moderate or high interest in the field of civic education “cultural/national identity”.

7) Interaction with authorities. This refers to the knowledge and skills that are responsible for the interaction of a person with authorities: understanding the state structure (legal institutions and their interaction), electoral participation, building transparent interaction, advocacy/lobbying, nonviolent resistance, change management, understanding of democratic views and values.

The respondents who defined their need in this area as “acute” make up 17,4% of the respondents (the lowest indicator among all areas). The respondents experiencing a “strong” need made up 33% of the respondents. “Moderate” need was noted by 32,2%. “Weak” need was noted by 16,6% of the respondents. The lack of need was noted by 0,9% (the lowest indicator in all areas). In total, 82,6% of respondents noted that they have moderate or high interest in the area of civic education “interaction with authorities”.

8) Understanding of the world context. We understand this as the knowledge and skills that help a person to interact with the world: cultural education, understanding the principles of sustainable development, building an information society, respect for other cultures and ethnic groups, knowledge of world history, understanding the context and mechanisms of international relations, intercultural communication.

The respondents who defined their need in this area as “acute” make up 20,2%. The respondents experiencing a “strong” need made up 29,3% of the respondents. “Moderate” need was noted by 33%. “Weak” need was noted by 12,9% of the respondents. The lack of need was noted by 1,9%. In total, 82,5% of respondents noted moderate or high interest in this area of civic education.

9) Environmental education. For this group, we have collected the knowledge and skills that are responsible for interacting with nature: environmental protection, nature management, waste separation, humane treatment of animals.

The respondents who defined their need in this area as “acute” make up 15,6%. Respondents experiencing a “strong” need made up 32,1% of the respondents. “Moderate” need was noted by 34%. “Weak” need was noted by 14,7% of the respondents. The lack of need was noted by 3,7%. In total, 81,7% of respondents noted moderate or high interest in this area of civic education.

Summing up the answers to the first complex question, we can say that, on average, 79% of respondents have a stable moderate or high interest in all areas of civic education offered in the survey. The greatest need is observed in the field of “personal growth” – 88%, and the least expressed need was in the field of “family formation” – 70,7%.

During September-November 2022 we interviewed 115 Ukrainian refugees in Europe (Poland, Lithuania, the Czech Republic, Germany, Finland) using the same methodology. We do not claim to be representative, however, based on the data received, we can talk about certain trends or hypotheses regarding the educational needs of refugees from Ukraine in citizenship education.

What changes can we state in these blocks of citizenship education:

- Human rights and freedoms. A decrease in demand compared to the pre-war situation by 7.6%.

- Personal growth. Зниження потреби у порівнянні з довоєнним станом на 5%.

- Communication. Increase in demand by 14%.

- Family formation. Increase in demand by 5,5%.

- Community formation and development. Decrease in demand by 9.2%.

- Cultural/national identity. Decrease in demand by 6.5%.

- Interaction with authorities. Decrease in demand by 12%.

- Understanding of the world context. Increase in demand by 11.2%.

- Environmental education. Decrease in demand by 5.8%.

As we can see, the results of the study showed growth only in the blocks of educational needs “Communication” (14%), understanding the world context (11.2%) and “Formation of a family” (5.5%). For all other blocks, it is possible to state a decrease in interest, with the largest decrease in the block “Relations with the authorities” (12%) and “Formation and development of communities” (9.2%).

Developers of citizenship education courses for refugees should pay attention to these trends.

In addition to surveys using anonymous questionnaires, we also conducted several focus groups in Poland, Lithuania, and Germany, in which we discovered the difference in educational needs of those who recently left Ukraine and those who stayed in the new country for more than six months. Among those who have lived in a new country for a longer time, there is a greater interest in citizenship education in virtually all its blocks, including legal literacy, protection of human rights, the country’s legislation, and participation in the life of local communities.

There is an even greater difference in the educational needs for citizenship education of those who decided to stay and integrate and those who are determined to return.

Those refugees who are interested in integration into a new country show a need for long-term educational courses, including citizenship education. Forced migrants determined to return to their homeland are only interested in short-term educational courses. It also applies to professional and citizenship education.

Another survey was conducted among civic educators to find out their needs for expert support. The results showed that in relation to the first set of questions dealing with issues of relevance for work with migrants/IDPs there are three main areas of work: work with migrants themselves related to their integration into local communities (such as Facebook news and opposition to it, language courses, job search courses, financial management, legal literacy, etc.); work with migrants to preserve their national identity (language courses, job search, financial management, legal literacy, etc.).

They also work with migrants to maintain their national identity (language courses, cultural workshops, support for music, art and crafts activities, concerts and master classes); Advocacy/awareness about migration issues and perceptions of other cultures in local communities (anti-freedom news, training of local groups of experts – journalists, lawyers, educators, civil servants and educators and other groups working with migrants).

The main difficulties that educators face in implementing educational programmes with migrants include low awareness of migrants about educational programmes, problems with organisation and participation (time and venue, low online coverage), low motivation and low participation.

The need to explore new needs and create new programmes based on these needs is highlighted. However, due to the weak institutionalisation of migrants in local communities, this kind of feedback is often difficult to obtain.

The survey involved 46 respondents from six countries (Armenia – 7, Azerbaijan – 7, Belarus – 10, Georgia – 5, Ukraine – 13, Moldova – 2 and Russia – 2). 87% of respondents are representatives of non-formal education, 13% – work simultaneously in non-formal and formal education.

The survey has been funded by the Federal Agency for Civic Education using funds appropriated by the Federal Foreign Office, Expanding Cooperation with Civil Society in the Eastern Partnership Countries and Russia (Eastern Partnership Programme).